A million-solar mass dark object detected at cosmological distance

John McKean

However, there are several competing models for what dark matter could be, whose predictions diverge is on sub-galactic scales (< billion solar mass clumps of dark matter); at such mass-scales, the number of dark matter clumps we expect to observe can change by orders of magnitude, depending on whether the dark matter is cold or warm. As dark matter does not emit any light, detecting low mass dark matter haloes is extremely challenging.

A novel method for such studies is gravitational lensing, where the light from a distant object is distorted by an intervening mass distribution. This process is purely dependent on gravity, and so, can be used to find and characterise dark matter haloes, even if they have no detectable light. This methodology has been successfully used to study several dark matter dominated objects at cosmological distances using high angular resolution imaging with the Hubble Space Telescope and with the adaptive optics system of the W. M. Keck Telescope. Although informative on the nature of dark matter, their masses (of order hundreds of million to a billion solar masses) were too large to conclusively discriminate between cold and warm dark matter models; for this, we need to detect even lower mass haloes, which, due to the small distortions that would be produced, requires angular resolutions of order a few milli-arcsecond.

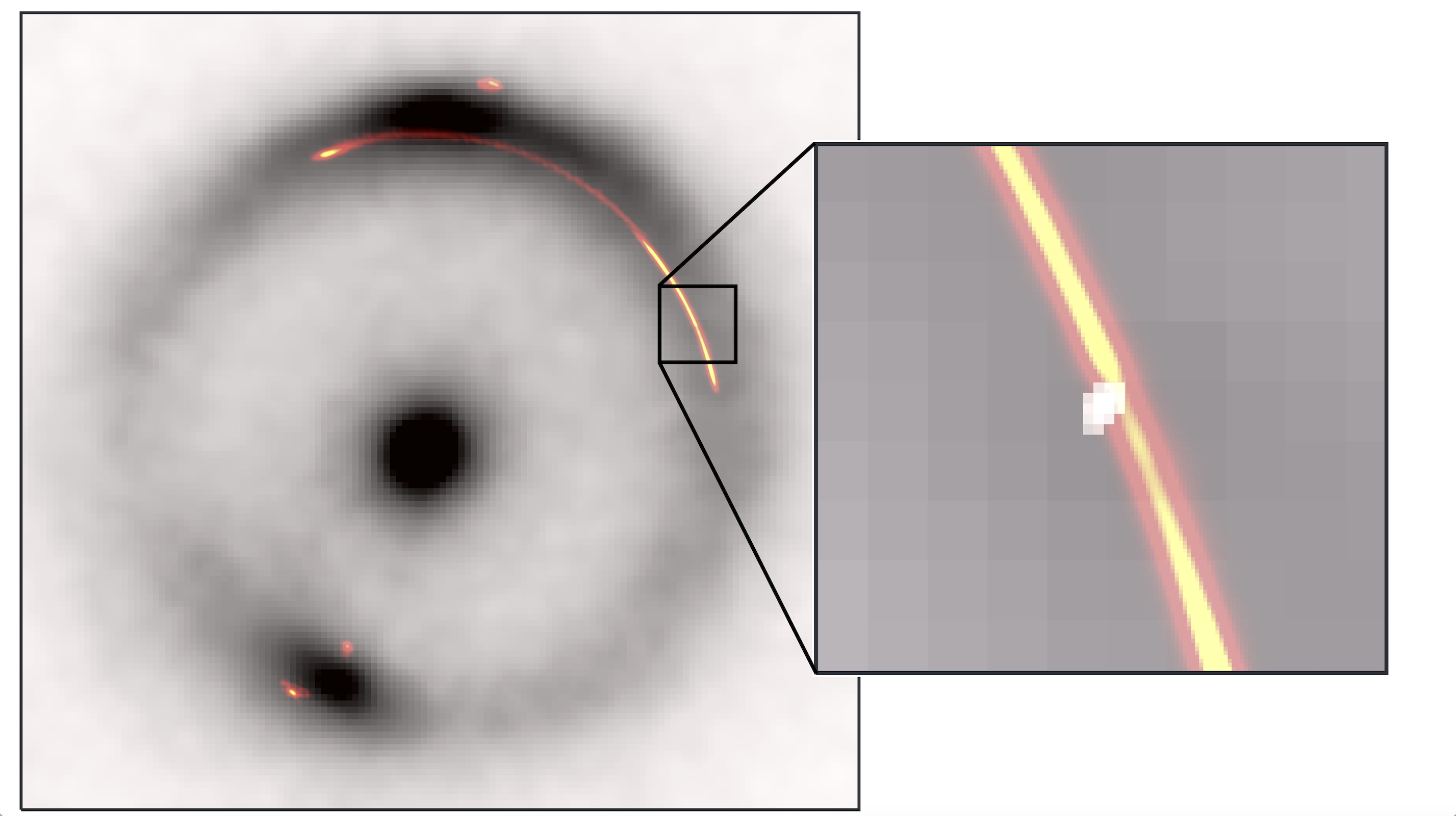

Using a global VLBI array that included the telescopes of the EVN, McKean et al. (2025) observed at 1.7 GHz the gravitational lens system JVAS B1938+666. The VLBI imaging fully resolved the lensed images (see Figure 1) and revealed a spectacular and extremely thin gravitational arc. After carrying out a gravitational lensing analysis of the data, a model for the unlensed source surface brightness was made. This showed that the object was a likely Compact Symmetric Object (CSO) of type-II at redshift 2.059. The two mini-lobes of the CSO are separated by 642 parsec and show multiple hotspots with brightness temperatures of order a billion Kelvin. By considering the surface brightness distribution of the radio source and other multi-wavelength data, McKean et al. (2025) concluded that the properties are consistent with the bow-shock model for compact radio sources.

However, as part of the modelling process, it was also found that one of the lensed images showed a gap in the gravitational arc. Using a novel methodology called gravitational imaging, Powell et al. (2025; Nature Astronomy) detected an additional object that has a mass of just 1.13 million solar masses (3.3% fractional uncertainty) within a radius of 80 parsec. The object has no optical emission, and so, was only detectable using the gravitational lensing technique, which is extremely robust (26 sigma). The probability of such an object being in the area of sky containing the observed gravitational arc is consistent with the expectations for the cold dark matter model. The object is currently the lowest mass to be found at cosmological distance, by over two orders of magnitude, and this was only possible due to the excellent sensitivity and angular resolution provided by VLBI.

Figure: Overlay of the W. M. Keck Telescope infrared emission (black and white) with the radio emission (colour). The dark, low-mass object is located at the gap in the bright part of the arc on the right-hand side, but is not luminous at infrared or radio wavelengths. The zoom in shows the pinch in the luminous radio arc, where the extra mass from the dark object is gravitationally ‘imaged’ using sophisticated modelling algorithms. The dark object is indicated by the white blob at the pinch point of the arc, but no light from it has so far been detected at optical, infrared or radio wavelengths. Image credit: John McKean; Keck/EVN/GBT/VLBA.

Link to the papers:

McKean et al. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnrasl/slaf039

Powell et al. (2025) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-025-02651-2

Contact:

John McKean, University of Groningen, University of Pretoria, South African Radio Astronomy Observatory. Email: john.mckean@up.ac.za